A Swan Lake

The Digital programme booklet

”The Stealing of the Veil“

The fairy-tale model from the collection of Johann Karl August Musäus for Johan Inger's new creation of A Swan Lake

A synopsis by Regina Genée, Ballet Dramaturge

During the war, the young soldier Friedbert, inexperienced in love, arrives at a chapel by a lake in a forest near Zwickau, where he meets an old hermit named Benno. The latter offers the young man shelter, makes him his successor and, shortly before his death, finally tells him about the mysterious swan girls who from time to time play at the lake. He relates that he was once in love with one of them, Zoe, but lost her a long time ago, which is why he has been living in solitude ever since.

One day when the swan girls are back at the lake, Friedbert watches the bathers and falls in love with the young Kallista. In order to get to know her personally, he steals her veil, preventing her from flying away, hides it, and tells her that a magician must have stolen it. Friedbert's plan is successful: unaware that he is the thief of her veil, Kallista takes refuge in the hermit's hut and gradually places more and more trust in her purported rescuer. Eventually, the two also begin a love affair and she agrees to follow him home to his widowed mother. However, Friedbert's mother knows his secret as well as the hiding place of the veil.

Shortly before the wedding, she finally tells Kallista about the theft of the veil and thus of the deception on the part of her son. Angry at Friedbert's treachery, Kallista takes back her veil and flies away as a swan. Friedbert then sets out to find her. He arrives on her home island of Naxos and meets her mother, Queen Zoe, who turns out to be Benno's lost lover.

Before her marriage to the hot-tempered King Zeno, she was also a swan maiden, but her husband punished her by tearing her veil. As a result, she was no longer able to fly to the Zwickau region, on the one hand to see Benno again and on the other to retain her youth, which would have been preserved by a regular bath in the magical Swan Lake. For this reason, Zoe became mortal and progressively weaker with age.

The Queen welcomes Friedbert and asks him to choose a bride from among the most beautiful girls on the island, but he refuses because his heart belongs to Kallista alone. He begs Zoe to be allowed to meet her. When he is finally able to enter her room, he asks for forgiveness and Kallista forgives him. Then they get married and live happily ever after.

The Stealing of the Veil © Rudolf Jordan (1842)

How do you approach your rehearsals?

You have to be extremely transparent and go into rehearsals with an artistic vision, but also be open to input on the part of the dancers. Forming the scenes and shaping the characters has to develop during the process. The more you dive into a role, the clearer you become about its different facets. In the beginning, it is quite two-dimensional work that starts on paper, but you have to bring that stage character to life, give it a personal background and make it three-dimensional. I have no concrete idea of the characters; but their complexity grows during the creative process.

How did you approach your new musical version?

It was hard to find out which musical number could illustrate our dramaturgy, but we definitely wanted to stick to Tchaikovsky’s ballet score. However, we decided to cut numerous variations, since we wanted our storyline to be carried and pictorially supported by Tchaikovsky’s music. The part that I like the most is the ”White Act“, i.e. the swan scenes, which evoke a mysterious and magical atmosphere.

A Swan Lake is about toxic relationships …

Yes, or the questioning of the form of love relationships. I think it is a theme we can all live through or be raised in. So, it speaks to our life experience. Of course, it is complex to develop a relationship with the right partner. And this is basically what all my work is about: human behavior and relationships.

”Taking on ‘the ballet of ballets’“

Choreographer Johan Inger on his new creation A Swan Lake

By Regina Genée, Ballet Dramaturge

What was your first general experience with Swan Lake?

This ballet was the first piece I ever danced when I was an eleven-year-old ballet student. In that rather classical version, I played a jester at the palace. At the age of 16, I portrayed one of the followers of Rothbart. Since then, Swan Lake has followed me throughout my dancing career and I associate it with a great deal of memories.

What makes Swan Lake appealing to you as a choreographer?

If you take on a ballet that is so famous, there is a performance tradition, an expectation – and a possibility to surprise. Actually, I assumed that that I should stage Swan Lake later in my life, since with A Swan Lake, I am devoting myself to ”world-famous ballet repertoire“ for the very first time. For this reason, I deliberately first created my own narrative ballets such as Carmen and Peer Gynt. And to me, Swan Lake is in fact ’the ballet of ballets‘. I think it can be thrilling and at the same time challenging to look at such a work from a different angle or to change the viewers’ perspective. Thus, we now refer to The Stealing of the Veil, a source on which the very first Swan Lake (1877) was supposed to have been based.

How did you become aware of this material?

It was my production dramaturge Gregor Acuña-Pohl who drew my attention to this fairy tale, and it was the former ballet director Aaron S. Watkin who had invited me because we talked about Swan Lake many years ago. Having discussed The Stealing of the Veil with Gregor, I thought it would be interesting from a historical perspective to actually visualize both where the very first Swan Lake was probably derived from and the differences between it and even more common 1895 version by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov. In addition, I was curious about the constellation of the characters: Whereas the ”tradition“ portrays the adventures of Prince Siegfried, The Stealing of the Veil – and thus our ballet version – focuses on the female leads. Last but not least, we were also fascinated by the local connection of the fairy tale to Germany and Saxony in particular, since after all, the cities of Zwickau and Dresden are not so far apart.

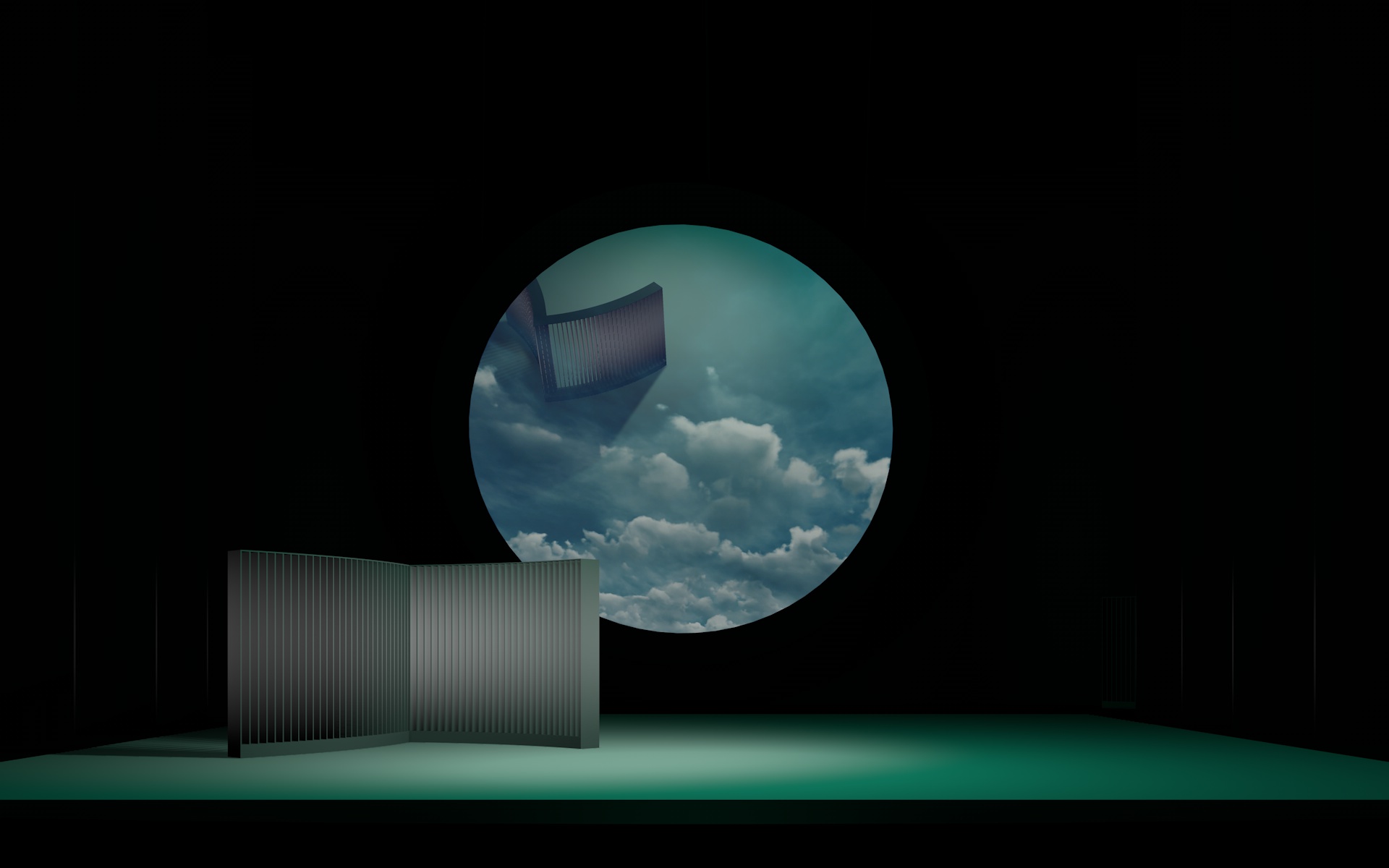

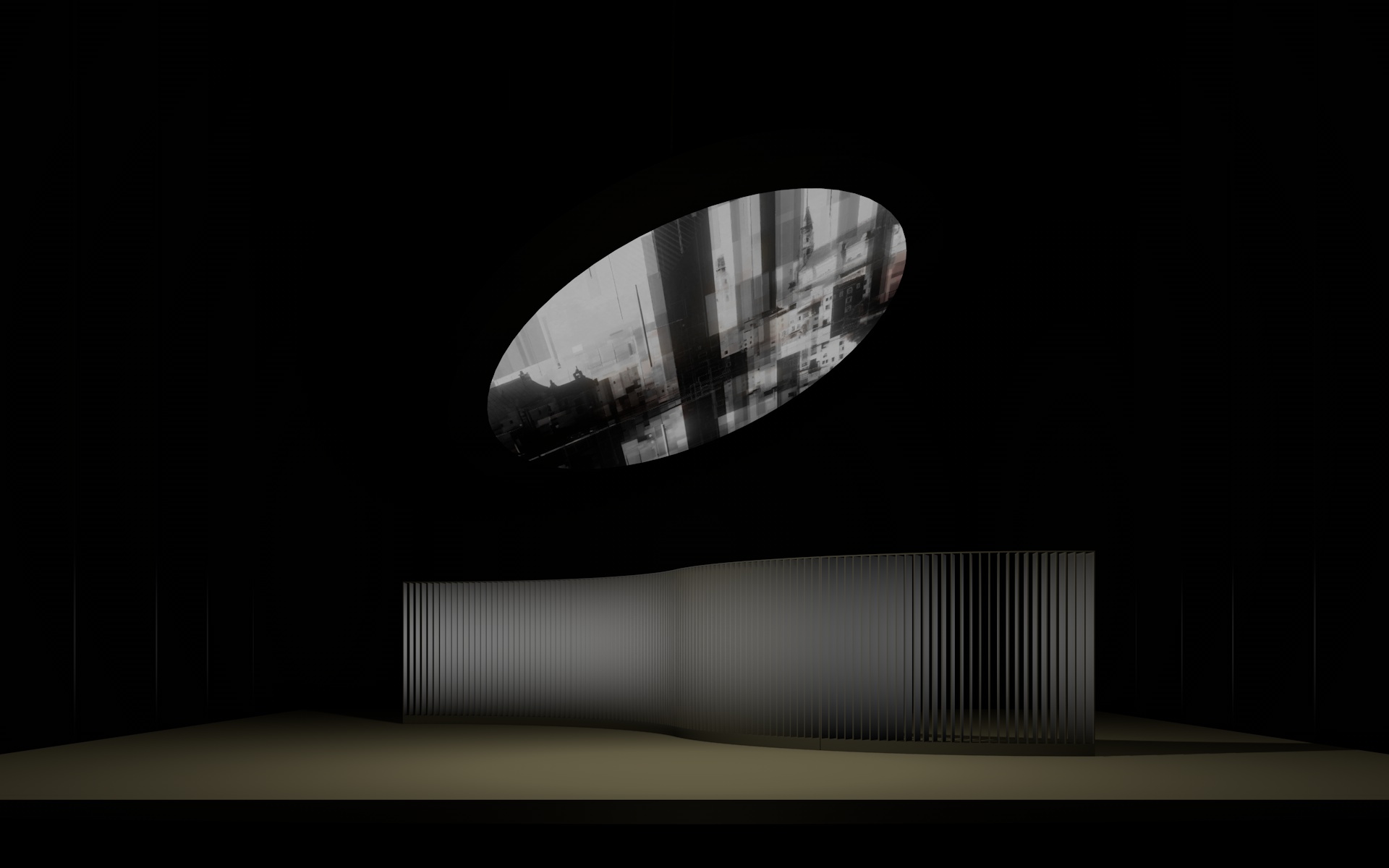

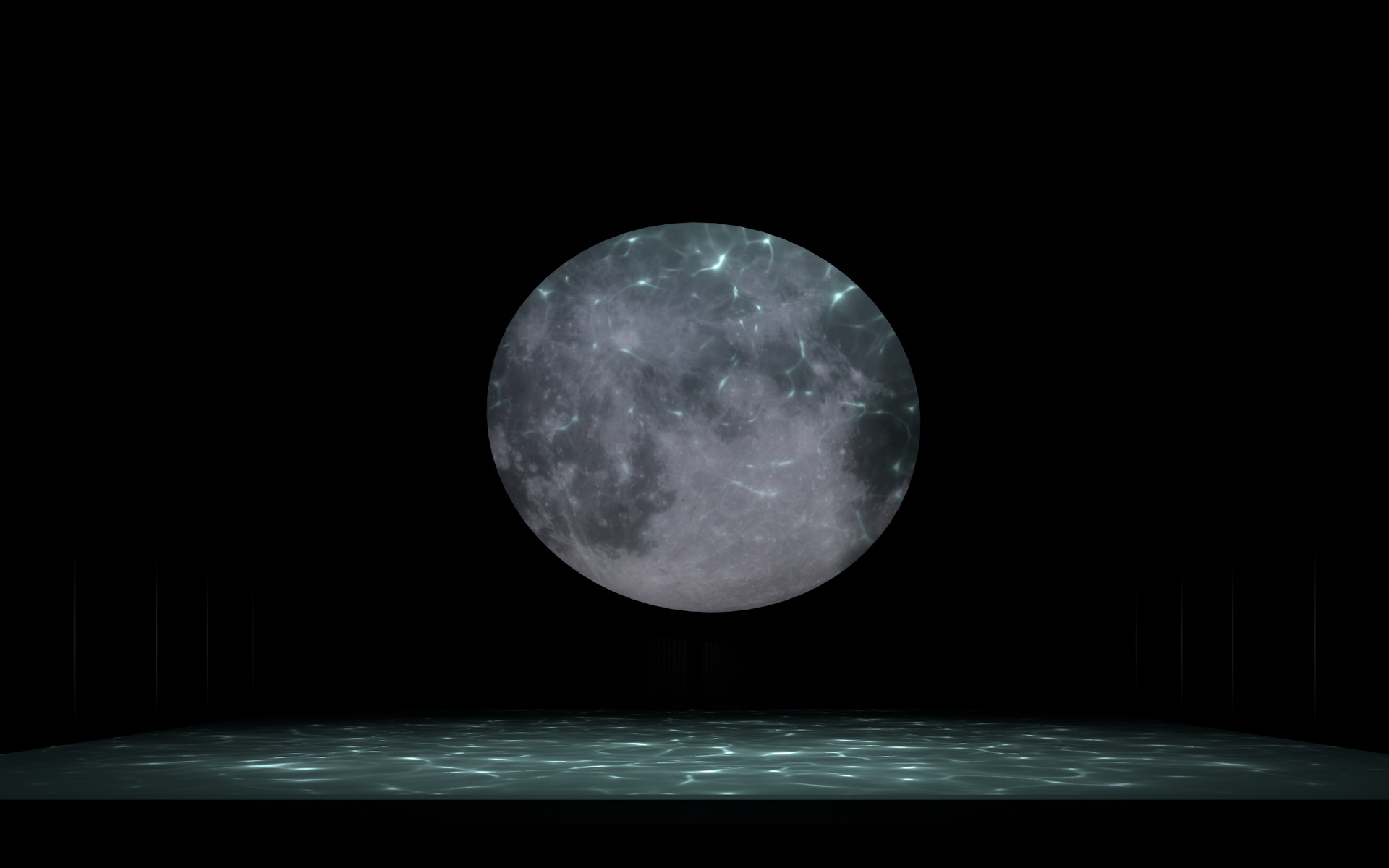

Scenographically, however, we chose to turn away from realism and worked on the idea of creating an illusory space – a dream world with an interplay between illusion and reality – which is at once restricting and liberating. With its plasticity, our minimalist aesthetic, both poetic and functional, aims to support Johan Inger's choreography and thus also opens up a whole new reading of this ballet classic to the audience.

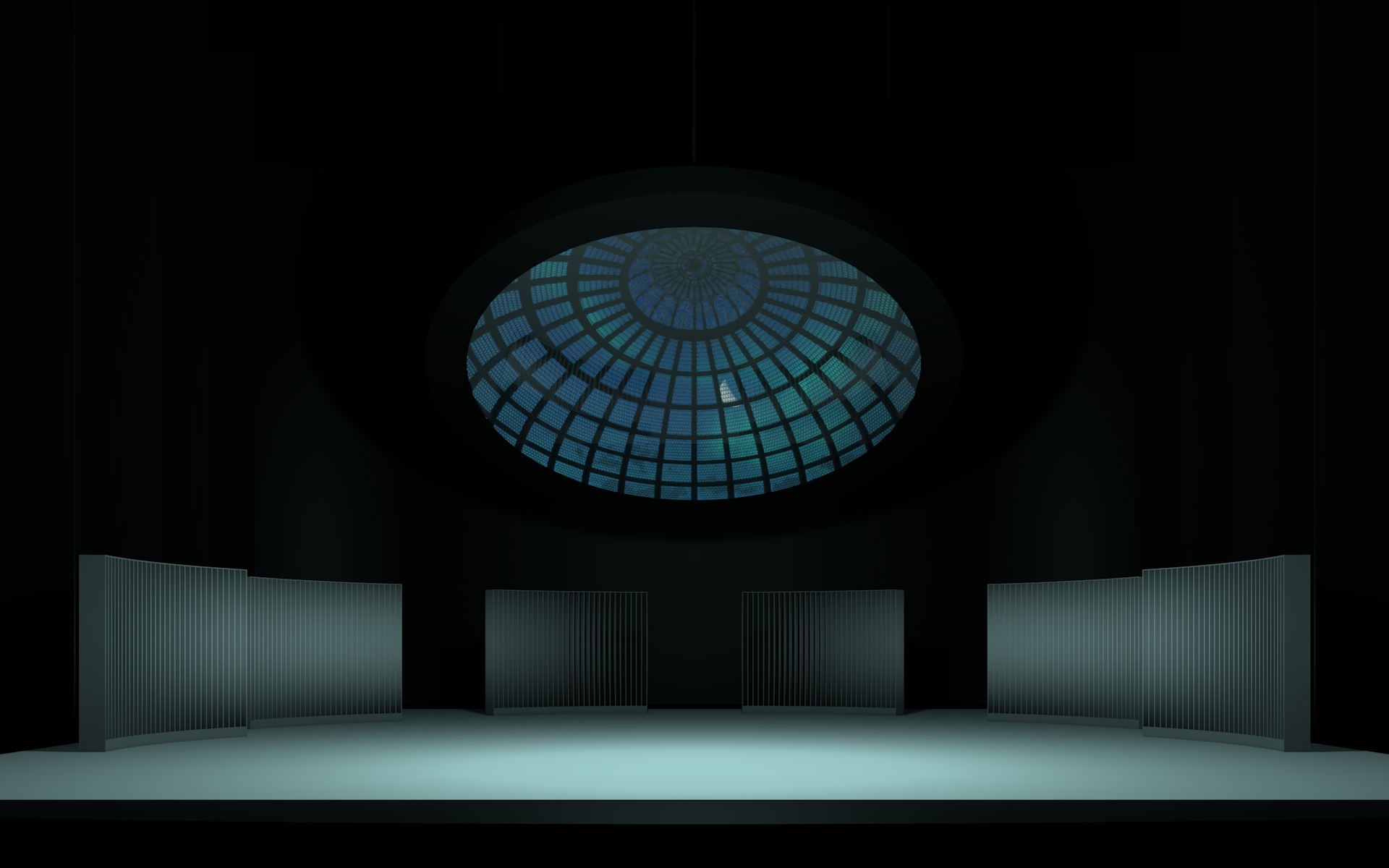

This idea is implemented on two spatial levels: a floating, ethereal, dreamlike, imaginary, and mobile upper level and a more formal, architectural lower level which can be transformed into different configurations by the dancers.

Fotos: EstudiodeDos; Leticia Gañán, Curt Allen Wilmer und Emilio Valenzuela Alcaraz (Videodesign)

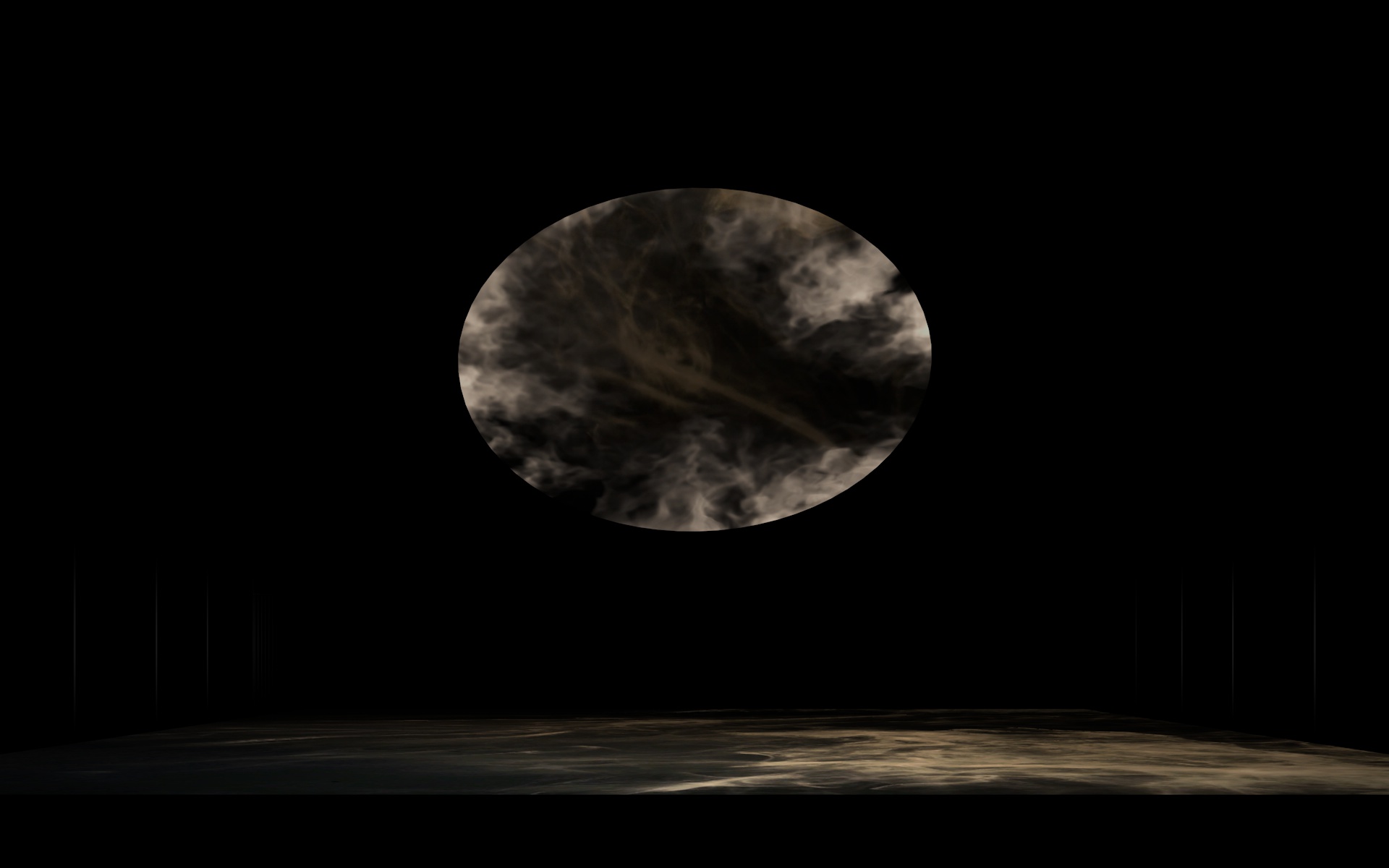

Set Design after the war

Set Design Hermit Hut at the Lake

Set Design Palace

Bühnenbild zu Bennos Reise

Set Design A Swan Lake

From the flies …

The upper level consists of a round mirror with a diameter of 9.50 meters. It is suspended at three points on winch motors and can move choreographically in different directions and angles. In it, we can see the nighttime moon at the lake, the surface of its water, or another ”visual space“ which can be perceived as such only by the theater audience but not the stage characters within the action. In this way, we also include the topic of ”voyeurism“, which is of essential importance in Musäus’ fairy tale original. This mirror is also translucent and has PVC film on the back onto which images can be projected. This means that the mirror not only reflects the images, but also makes them visible. In this way, we can create visual illusions that connect different perspectives: the mirror reflects the images projected onto the floor, mixes them with those that appear behind the mirror, and the whole merges with the reality of the dancers' moving bodies. It all depends on which light intensities are used and whether or to what extent they are mixed to create different dream images. Technically, one projector has to project onto the mirror film from behind, and two more onto the floor in front in order to create these images. It is important that the dancers are additionally illuminated with light from the side wings.

… to A Swan Lake

On the lower level there are three large movable partitions which can be divided into six smaller ones. These are curved walls – consisting of wooden slats – that permit a certain transparency. The dancers push the walls into different positions, allowing many rooms and landscapes to be portrayed. Together with various lighting effects and the dancers’ movements, we again evoke the aspect of (secret) observation, which can relate to both the characters on the stage and the theater audience: whether it is the bars of a prison cell, interior walls of a house, reeds on the lake, or house facades on the roadside – we open up many possibilities of interpretation for the audience.

Between illusion and reality

On the set design concept of Johan Inger's A Swan Lake

By Leticia Gañán and Curt Allen Wilmer, EstudiodeDos

Since this new choreography of the ballet Swan Lake is based on the fairy tale The Stealing of the Veil from the collection of Johann Karl August Musäus, our set design includes several realistic spaces from the German folk tale: a palace, a terrace or a garden in front of the palace, a prison, a vision of A Swan Lake, a war scene, a house, etc.

„Leda’s daughters do not, like those of common mortals, make their entry into the world stark naked, but have their delicate bodies cloathed in an aerial garment, formed of condensed light“

– Theophrastus from The Stealing of the Veil–

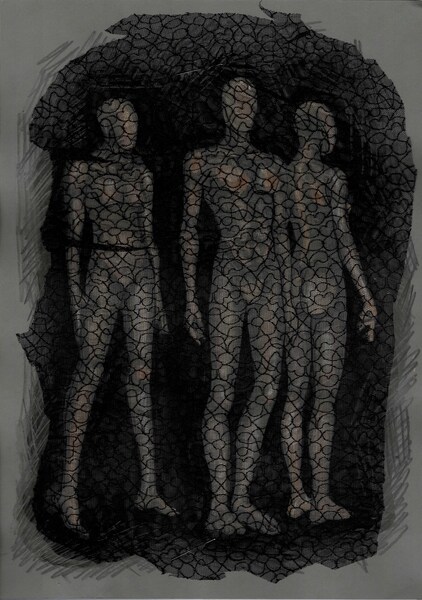

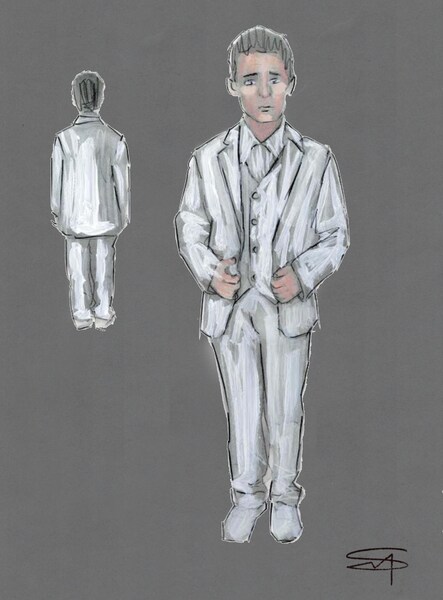

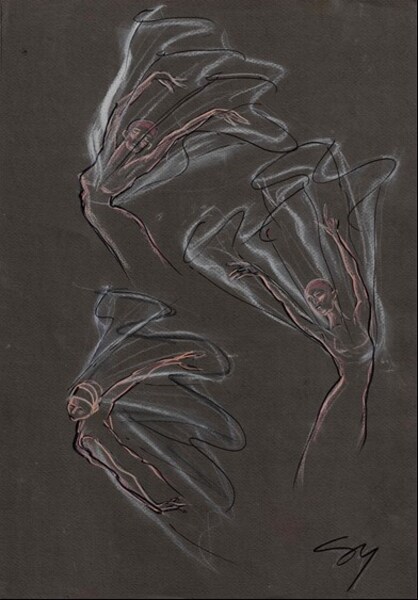

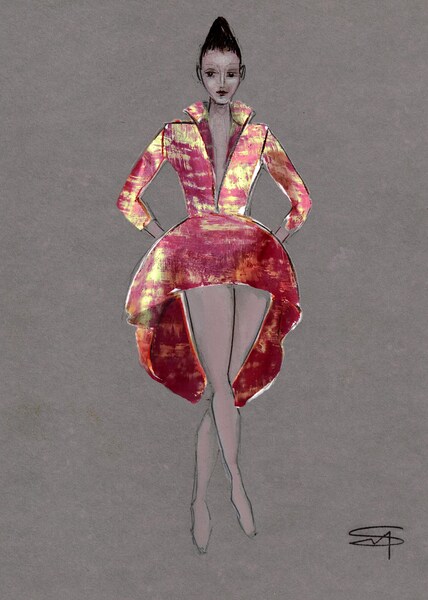

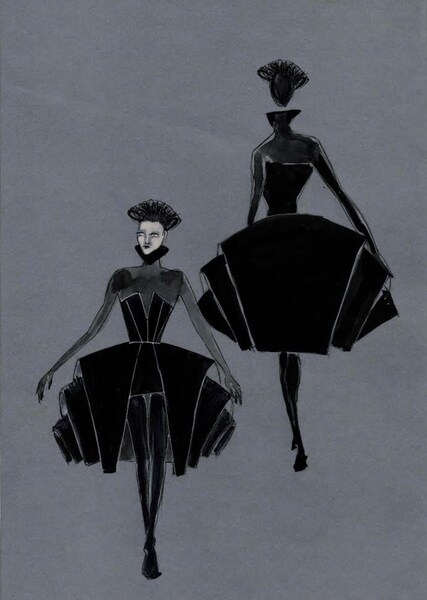

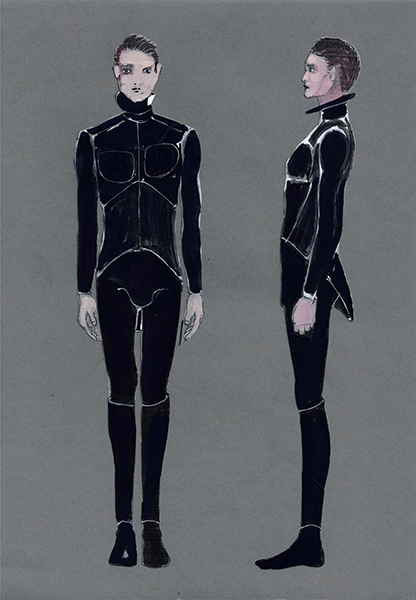

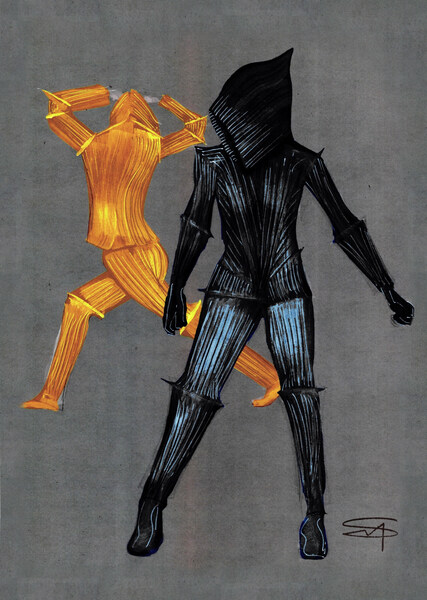

Figurines by Salvador Mateu Andujar

As a costume designer, what appeals to you about creating for dance?

The challenge of creating a universe that accompanies movement, dramaturgy, space and musicality.

Johan Inger's reinterpretation is based on the German folk tale The Staling of the Veil. What do you associate with this interpretation?

I remember my home country Spain that is still steeped in tradition and religiosity; the portable chapels with little virgins that the neighbours passed from house to house, my great-grandmother and my grandmother with their black veils as a sign of mourning, the mantillas at Easter. The veil for me has a deep connection with mystery and magic. When I was five years old, I visited a small village in Teruel, Aragon. My mother stopped at the door of the church because she was not dressed appropriately. However, a lady from the village took a tablecloth from the altar and wrapped it entirely around her. Then, my mother was allowed to cross the threshold and to access the sacred space with a Virgin’s veil.

What does the music of Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake mean to you?

Tchaikovsky has an enormous capacity to evoke images and emotions such as fragility and symphonic strength that connect with the essential and the absolute, they move me deeply.

From the perspective of fashion history: why are veils and femininity so closely linked?

The relationship is ambivalent: orientalist sensuality, the veils of Salome or Helen of Troy on the one hand, or the wave of protest in Iran over the violent death of a woman for wearing the wrong veil … Fashion is also a reflection of the zeitgeist. In Inger's reinterpretation, the veil is a symbol of relief and freedom.

Swan people, as in Musäus's fairy tale, are chimeras of humans and animals. What is the challenge here for your costume design?

Representing the swans with the determination to avoid the iconic image so deeply rooted in the collective memory – the Tutu or the feathers – is a challenge, and the name of the tale the best clue to follow. In Johan Inger's version of Swan Lake, the veil is a magical tool of transformation that confers powers such as the ability to fly to a lake where you can fulfil your innermost desires and to go beyond the veil of appearance to be yourself.

To what extent are costume design and choreography connected?

It is a close and inseparable relationship with the choreographer and dramaturge. I aspire to create an aesthetic universe, a dramaturgy through the costume that makes it easier for the audience to identify the characters and that represents a performative tool adapted to the choreographic functionality.

How did you go about choosing the colours and fabrics for your costumes?

The colour black is reserved for the court, inspired by the distinction and sobriety of the court of Philip II. Zoe’s clothing ranges from red and gold to black, as a sign of mourning. The main characters require sobriety, and, generally speaking, my costume design is quite restrained, whereas the golden yellow of the soldiers at war is highlighted.

The essence of Johan Inger's new creation is the importance of equality and freedom in interpersonal (love) relationships. What does ”love“ mean to you?

It is a universal feeling that is difficult to explain. I think it has to do with respect for who you are and total acceptance of the other. Unlike money, the more you give the more you have.

Production photos Nicholas MacKay; Workshop photos: Nadja Möller

Plot and musical overview

The following table combines the number and titles of the scenes from Johan Inger's A Swan Lake libretto in chronological order of the plot with the numbering and musical indications from Tchaikovsky's score. Its content and structure of the Dresden premiere can be seen as follows:

Akt I

Scene | Place | Score |

0 | Prologue: Limbo | Introduction |

1

| Ballroom | 1. Scene (Allegro giusto) |

Walz | 2. Walz | |

2 | Terrace | 3. Scene (Allegro moderato) |

3 | Prison | 19a Pas de deux I. Moderato - Andante |

4

| Journey | 19b Variation I. (Allegro moderato) |

Italy | 22. Neapolitan Dance | |

Spain | 21. Spanish Dance | |

Hungary | 20. Hungarian Dance (Czárdás) | |

5 | Scene change | 13. (Dance of the Swans), II. Moderato assai |

6

| A Swan Lake | 10. Scene |

Swans | 13. (Dance of the Swans) V. Pas d'Action, Andante | |

Farewell | 13. (Dance of the Swans) VII. Coda, Allegro vivo | |

7

| Back at the Palace | 15. Allegro giusto |

Zoe’s return | 17. Scene | |

Dying Swan | 19. Pas de six, Variation II, Andante con moto | |

8

| Back at the Lake | 9. Finale I, Andante |

Intermission |

|

Akt II

Scene | Place | Score |

9

| 20 years later | 5. Pas de deux: I. Tempo di valse |

Dowager Queen | 5. Pas de deux: II. Andante | |

War Games | 24. Scene | |

10

| Go in and win | 13. (Dance of the Swans) I. Tempo di valse |

Battle | 13. (Dance of the Swans) IV. Allegro moderato | |

11 | Kallisto’s Healing | 4. Pas de trois, II. Andante sostenuto |

Like father and son | 19. Pas de six - Intrada | |

12 | The Secret | 14. Scene |

Odette | 6. Pas d'action | |

The Stealing of the Veil | 12. Scene, Allegro | |

The Saviour | 7. Sujet | |

13 | Lovers | 27. Dance of the Little Swans |

The missing Prince | 11. Scene, Allegro moderato | |

14 | Family Routine | 28. Scene |

Finale | 29. Final Scene |

With Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake, we firstly have an extremely extensive original score: four complete acts with a wealth of lively dances and enchanting melodies. Already in the 19th century, it was customary to make generous cuts in ballets, to exchange, supplement, or change the order of musical sections – even to have pieces or arrangements added by other composers. In a sense, Swan Lake is a historical turning point, since the music is quite symphonic and it includes no pieces by other composers.

The characteristics of the score

Whether as individual numbers or as an orchestral suite, the symphonic passages of Swan Lake, detached from their integration in the narrative ballet, have found their way into the concert repertoire. Examples include the large-scale waltz, the delicate adagios in the pas de deux, and the lively national dances (such as the Hungarian cszárdás, the Spanish bolero, and the Neapolitan tarantella) as well as the distinctive variations, spirited polonaises, marches, etc.

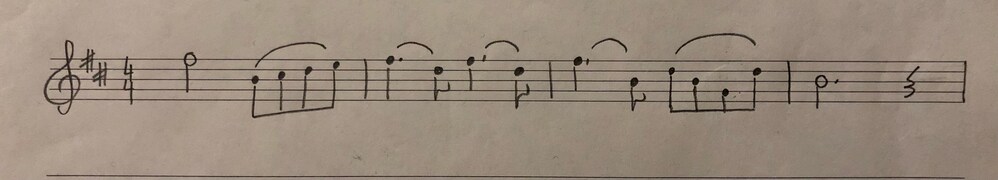

However, the famous Swan Lake motif stands out in particular, running as it does through the entire work like a leitmotif: longingly played by the oboe over harp arpeggios and a tremolo in the strings and based on a simple note sequence above the B-minor triad (B - D - F-sharp), it has a special magic. Already in the very first bar of the score, it is suggested by the solo oboe in the modified form of a descending note sequence, points, as a kind of ”musical framing“, to a tragic end, and lends the entire work a fundamentally melancholy character. Interestingly, this musical beginning is identical to that of the fourth movement of Tchaikovsky's 6th Symphony, the Pathétique – merely a coincidence…? During the course of the action in Swan Lake, this theme will be heard again and again: sometimes in delicate pianissimo, sometimes in dramatic fortissimo, and at the very end in a grand apotheosis played by the full orchestra in the radiant B-major variant (B - D-sharp - F-sharp) in triple fortissimo. This one melody and its ingenious dramatic use within the score have certainly contributed much to the fact that Swan Lake has become so famous.

Music example Swan Lake motif © Thomas Herzog

The Dresden version 2023/24

For the story adapted by Johan Inger for A Swan Lake, the first challenge was to select the musical passages that would inspire the choreographer the most, and at the same time be best suited for the drama in order to compellingly convey the plot of The Stealing of the Veil. Since the goal was a two-act performance with only one intermission, this inevitably meant leaving out several numbers, as attractive as they are. An equally demanding task was to arrange the new order of the individual selections as judiciously as possible so the transitions seem natural. With this aim, it was necessary to transpose certain passages into a different key, to add a few measures for the purpose of modulation – i.e. transition – or to find the optimal musical juncture point by omitting a few measures. The ultimate goal was to ”intervene“ as little and prudently as possible in order to maintain Tchaikovsky's original musical character as much as possible.

Thomas Herzog © Lucia Hunziger

The ”classic Swan Lake“

The work underwent changes of a completely different kind after Tchaikovsky's death. The director of the Imperial Theater commissioned Tchaikovsky's brother Modest to revise the libretto for a new production by the choreographers Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov. Modest Tchaikovsky, who found the original libretto ”so badly done“ that he ”had to change the entire text“, shortened the four acts to three and made a number of significant changes: certain parts of the story were simplified or completely removed and important roles were eliminated or their character changed. For example, Prince Siegfried is now changed from the macho of the original to a noble hero who himself becomes the innocent victim of an intrigue in which Odile pretends to be Odette. Modest also drastically modified the ending: he softened the tragic end of the original by uniting the two lovers, who are transported away into a fantasy world. This version also did not pay much care to the composer's musical conception. Again, musical numbers were changed, shortened, and supplemented by some of Tchaikovsky’s piano pieces which the conductor Riccardo Drigo specially orchestrated for the purpose. This new version was premiered on January 27, 1895 in St. Petersburg and gradually gained success with the audience. It soon became a model for later choreographies.

Original or arrangement?

When we talk about Swan Lake, we thus need to ask ourselves which version we mean: the one with the plot of the 1877 Moscow premiere (which Tchaikovsky used as his basis), or the much better known St. Petersburg version which was, however, not authorized by the composer? Are we referring to the original music or the variants arranged by others?

And finally, the now so popular staging of the antagonists Odette and Odile as white and black swans did not yet exist in Tchaikovsky's time. It was not until 1920 that Odile was first made to wear a black dress; this costume then prevailed from 1941 onward with the staging of the ”Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo“ at the New York Metropolitan Opera.

Ensemble Swan Lake Choreography by Aaron S. Watkin © Semperoper Dresden/Costin Radu

Black Swan in Swan Lake Choreography by Aaron S. Watkin © Semperoper Dresden/Ian Whalen

”Swan Lake“: Which ”Swan Lake“?

The laborious emergence of a masterpiece

By Ulrich Linke

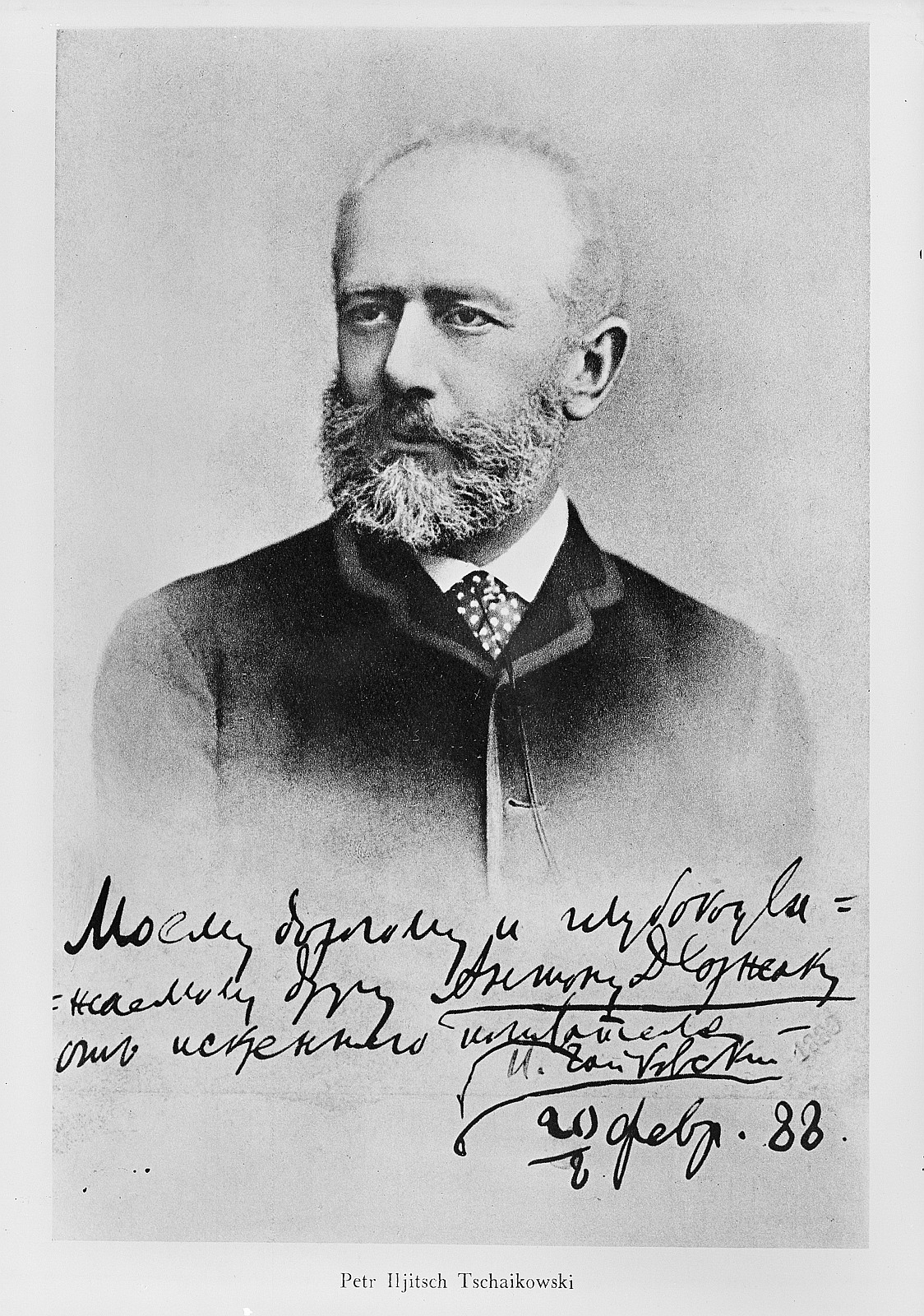

It is quite astonishing that a work like Peter I. Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, which is today considered the epitome of romantic ballet and rightly celebrated for its imaginative, colorful, and vivacious music, had great difficulty establishing itself in the repertoire during the composer’s lifetime.

The premiere on March 4, 1877 at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow in the choreography of Julius Reisinger received only lukewarm applause, and the dancers, orchestra, and set design were criticized. But Tchaikovsky's music was hardly appreciated either: it was said to be too loud, too Wagnerian, too symphonic, and too complicated for ballet. The libretto by the playwright Vladimir Begichev and dancer Vasily Geltser took up common fairy-tale motifs about enchanted swans – we recall, for example, the Greek myth of Leda and the Swan, Lohengrin, and Grimm's Six Swans, as well as Johann Karl August Musäus‘ The Stealing of the Veil, from which the librettists took at least one name, the German setting, and the motif of the enchanted princess. It proved difficult in this version that Prince Siegfried (the male protagonist), who initially falls in love with Princess Odette in swan form but is later seduced by her rival Odile, is a rather arrogant simpleton who would certainly not have conquered the hearts of his viewers. Even a new production in Moscow by Reisinger's successor Joseph Hansen (1880) was only marginally better received by the audience. Due to musical cuts and changes together with the replacement of certain numbers by other compositions, the score was increasingly distorted artistically. In the end – if Nikolay Kashkin is to be believed in his ”Memories of Tchaikovsky“ – ”almost a third of the music of ’Swan Lake‘ was replaced by insertions from other ballets, and mostly from average ones at that.“

Pyotr I. Tchaikovsky – A Stranger in Russian Society

By Benedikt Stampfli, Dramaturge

Pyotr I. Tchaikovsky was born on May 7, 1840 in Votkinsk in the Urals, the second son of the engineer and lieutenant colonel Ilya Petrovich and his second wife Alexandra Andreyevna. His mother was the granddaughter of the French sculptor Michel Victor Acier, who worked as royal Saxon master modeller at the Meissen porcelain factory. Music played an important role in the Tchaikovsky family, in which their mother taught the children to play the piano and did a great deal of singing. While Tchaikovsky's mother only spoke French to the children, his father brought Ukrainian culture into the family. Tchaikovsky's grandfather Pyotr Tchaika was born in the Poltava region of Ukraine. During his studies at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, where he was trained as a regimental doctor, he changed his family name to Tchaikovsky.

Initially, Pyotr I. Tchaikovsky studied law in St. Petersburg for nine years before embarking on a new path and, from 1862, studying composition and instrumentation with Anton Rubinstein at the newly opened conservatory. Only three years later, after completing his studies and earning a diploma, he moved to Moscow.

In Moscow, Tchaikovsky wrote his first successful compositions, including his Symphony No. 1 (1866) and the Romeo and Juliet overture (1869). He travelled a lot, met other composers, and became acquainted with their aesthetics.

He also worked as a music critic and visited Bayreuth in 1876, for example, to attend the world premiere of Richard Wagner's Ring of the Nibelung. In the same year, he composed the ballet music for Swan Lake and met Nadezhda von Meck, a wealthy widow and sincere admirer who supported him generously from that point on.

In the late 1870s, Tchaikovsky set Eugene Onegin, based on the verse novel of the same name by Alexander Pushkin, which enjoyed a great success at the Bolshoi Theater in 1881. Tchaikovsky was not only a freelance composer whose fame was spreading more and more widely in Russia and Western Europe, but also increasingly worked as a conductor from 1878 onwards: on a major concert tour through Europe, he made a stop in Dresden in 1889 and conducted the Dresden Philharmonic, which had been founded less than 20 years earlier as the Gewerbehaus-Kapelle.

While Tchaikovsky was working on his penultimate opera The Queen of Spades, he also wrote other important works such as the ballets The Sleeping Beauty (1890) and The Nutcracker (1892), his Symphonies No. 5 and 6 (1888/1893), and the String Sextet Souvenir de Florence (1890). The score of The Queen of Spades features melodies, rhythms, and tonal colours from his other works. One can also find a close relationship his late symphonies in particular, but the 1812 overture (1882) is quoted too. On 19 December 1890, the Mariinsky Theater presented the premiere of The Queen of Spades – one of his greatest successes.

Crises and success

Tchaikovsky struggled with depression throughout his life; the main reason for this was his homosexuality, which was concealed from the public. In the late 1870s, he had one of his closest romantic relationships with Iosif Kotek, one of his former pupils at the Moscow Conservatory who was employed as a private musician by Nadezhda von Meck. From his letters to his brother Modest, we can guess how much the composer must have been on the brink of insanity and at risk of suicide due to his ”forbidden“ sexual orientation. Tchaikovsky had a very close relationship with Modest, not only because his brother wrote him several librettos, but for he was also able to reveal himself to him and talk about his feelings. Pyotr I. Tchaikovsky was an outsider himself and as such felt a close affinity with Hermann, the male lead in The Queen of Spades: ”Hermann [was] not only the reason for me to compose such and such music, but always a real living person of whom I am very fond.“

At the end of October 1893, he conducted the world premiere of his Symphony No. 6 in St. Petersburg. Only a few days later, on 6 November, he died of a cholera infection. Whether this was actually the cause of death remains a mystery to this day, because there is also the hypothesis that Tchaikovsky poisoned himself with arsenic because a ”court of honour“, consisting of members of the St. Petersburg law school where he had also studied, had asked him to take his own life due to his sexual orientation.

”Swan City“ Zwickau

By Benny Dressel, City Archivist Zwickau

„The situation of the Swansfield near Zwikow, in the mountains called, from the abundance of their ores, Ertzgebirge, is well known. The name is derived from a pool, entitled the Swan’s pool, which is at present nearly but not quite dried up.“

With these words begins the fairy tale that forms the basis for Johan Inger's A Swan Lake. But what, from a historical point of view, is behind the local connection to Saxony?

Zwickau and the swan are inconceivable without each other. Forever visibly connected in the city coat of arms displayed above the venerable town hall. However, as incredible as this association may be, upon investigating it, one inevitably encounters mythology. After all, history and mythology are loving sisters. Perhaps, for romantic reasons, it would be better to keep it that way. Just like the fairy-like early fog over the Zwickau Swan Pond on a cool autumn morning.

Historical documents show that the structural layout of the pond was approved in 1473 and its construction completed by 1477. In 1504, it was incorporated into the municipality and served as a defensive pond.

With the age of industrialization, the use of the Swan Pond, on the western bank of which the Swan Palace was built in 1836 (but which was demolished in the 1990s), grew as a day-trip destination for the Zwickau city population. In the mid-19th century, the ”Large Pond“ was supplied with swans, christened the ”Swan Pond“, and integrated into a larger green space. The Zwickau chronicler Emil Herzog, who wrote a city chronicle around 1840, assumed there was a connection with the district of Schwanfeld [Swan Field], as the region around Zwickau was formerly called.

A less rational explanation is provided by the mythological meaning of the swan, which has been associated with this Saxon district seat since the Middle Ages.

Wouldn’t it be appealing to think that the theologian Thomas Münzer signed his receipt in 1521 with a swan instead of goose feather, and then defiantly left Zwickau ”fighting for the truth in the world“? Martin Luther, who was in the city the following year, later became very annoyed with the ”wild people of Zwickau“ who were once so loyal to him, when the council did not comply with all his ideas regarding the interplay of ecclesiastical and secular power. Yes, swans can be very pugnacious when it comes to their brood.

Was Augustus the Strong reflecting more deeply in 1691 on the Electorate of Saxony, flourishing thanks to Zwickau, when, still without the burden of governing, he shot ducks ”for fun“ on the Large Pond (and later ”Swan Pond“)? What might the spirit of Zwickau's most famous son, Robert Schumann, have been musically dreaming of when his monument stood on the Swan Pond grounds for almost 45 years? So where is the root of this connection between Zwickau and the swan which is hovering about in everyone’s minds?

It is easily found in the figure of the then widely famous Zwickau mayor and chronicler Erasmus Stüler or Stella (1460–1521). Due to the lack of documents proving that the city of Zwickau was founded in ancient times, full of good intentions, he summarily fabricated a number of documents himself. Accordingly, Zwickau is said to be an ancient city whose founding dates back to the son or grandson of the Greek Hercules, named Cygnus (English: ”swan“), and which was therefore given the name Cygnea, Cygnau, or in German, Schwanfeld. Later chroniclers have destroyed the fantastic construct with scientific ruthlessness by proving through source research that Stella's documents are forgeries.

Postcard Swan Pond; Source: Zwickau City Archive

The reference to the swan may also be due to the fact that in the Middle Ages, it was considered an ”exotic“ animal which was rarely found in the region around Zwickau – this also bridges the gap to The Stealing of the Veil, which speaks of only three bodies of water where the swan creatures take their annual beauty bath. And the Greek swan queen Zoe flies with her companions to Saxony, nine days away.

However, one historical fact connecting the swan with the city of Zwickau is incontrovertible: In 1407, four Zwickau councilors paid with their lives for rebelling against the Meissen margrave and in defence of time-honored judicial law. Soon after their bloody heads were rolled on the courtyard cobblestones of the Meissen Albrechtsburg Castle, their tombstone was adorned with three swans and they were honorably buried at the Church of St. Afra. Here for the first time in Zwickau's history swans appear, and would remain.

The proud swan has always symbolised purity, faithfulness, and innocence. Was it a defiant statement of the bereaved against the unjust sentence?

Replica of the gravestone in the courtyard of the Zwickau Priesterhäuser © B. Dressel